Orientation

A Rigorous Foundation for a Productive Year

“Orientation was invaluable. At the time we didn’t realize how valuable it was to be.

As it turns out, our orientation is the envy of all those who work on the Hill.”

— Dan Clouser, 1986-1987 Fellow

From Concept to Structure

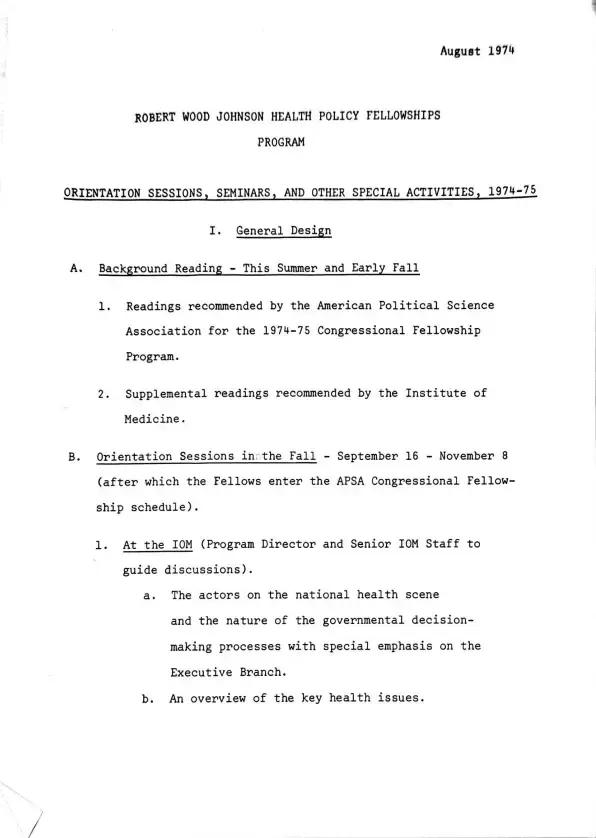

The RWJF Health Policy Fellows orientation is a meticulously crafted training experience, designed to prepare its fellows for a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s health policy. From the program’s first conception, a core training component was a critical piece of the proposal. Yet, what this training program would look like — who would lead it, what content would it focus on, and how long it would last — was an open question.

The original July 1972 proposal stated, “Fellows will enjoy a planned group educational experience which should systematically explore the interrelationships among the various arms of the Health Enterprise (or Industry) and all those governmental and non-governmental agencies and organizations which significantly influence public policy. It is likely that much can be learned in this area from the experience of the White House Fellows program which has been in existence for more than 5 years.”

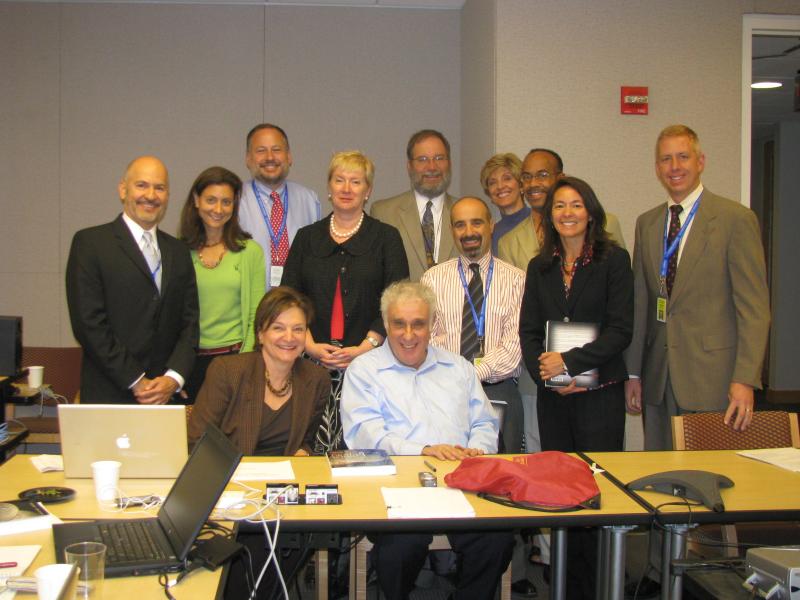

Orientation session in November 1975. NASEM Archives.

Orientation session in November 1975. NASEM Archives.

A document to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Trustees later that year gave more explicit recommendations. It proposed a two-part training program:

“[U]nder the first part the fellows would be enrolled in the Congressional Fellowship Program sponsored by the American Political Science Association, the principal scholarly society in the public affairs disciplines. The Congressional Fellowship Program provides the best practical learning experience now available in the country of how public policy is determined.

The second part of the proposed Foundation fellowship program would be seminars organized by the independent board established by the Foundation, and would take place during the fellows’ Congressional staff assignments. The board would be responsible for the development of a series of seminar sessions on issues in medicine and public policy, which would include participants from organizations such as the Institute of Medicine, the executive branch health agencies, and academic researchers in the public policy field.

Finally, in the March 1973 proposal to establish, the planning committee landed on a training plan that the program still follows today:

“Fellows would be expected to mọve to Washington, D.C. in time for the opening sessions, and to spend a period of six to eight weeks in an orientation program centered on matters of health and health policy organized by a staff based at the Institute of Medicine. This portion might include seminars to familiarize fellows with health agencies in government, congressional committees responsible for health affairs and the areas covered by each, problems and opportunities in health policy as viewed by the IOM staff and various IOM members, guest experts, HEW staff and congressional staff. Site visits to the various agencies might be scheduled. Insofar as it would be possible and consistent with the development of seminars, the preliminary program should be tailored to each fellow’s individual interests.

Following the IOM-sponsored period, the fellows would join the regular [American Political Science Association (APSA)] Congressional Fellows Program. They would be incorporated in the program along with fellows from the fields of political science and journalism. The Congressional Fellowship Program begins with a period of introduction to the Federal government and how it functions.”

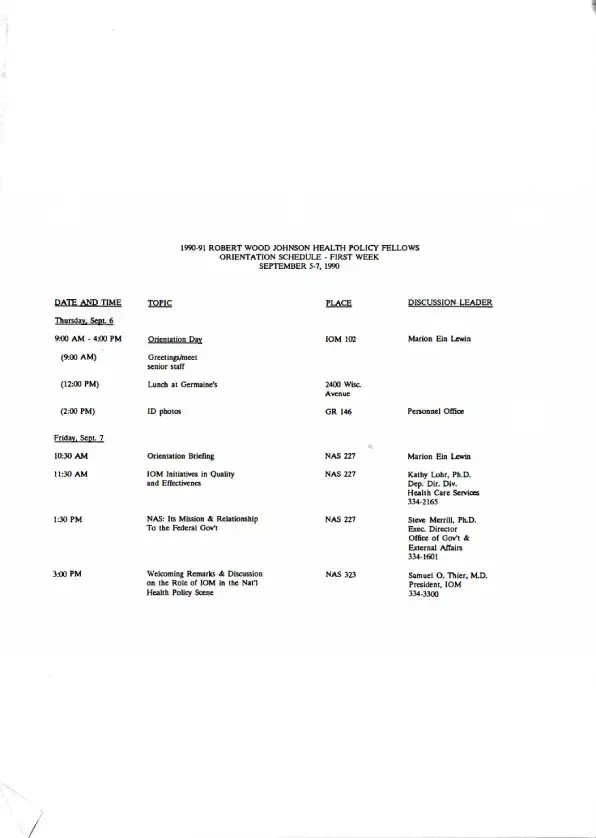

Today, orientation includes over 200 meetings with national leaders in health policy, think tanks and interest groups, key executive branch officials, and members of Congress and their staffs. The immersive orientation process covers health economics, the congressional budget process, priority health policy topics, and federal decision-making. The fellows also participate in activities, including executive coaching and media training sessions to help prepare them for their placements and future work in health policy. The briefers and schedule change every year in response to the changing health policy landscape and recommendations from the previous fellowship cohort.

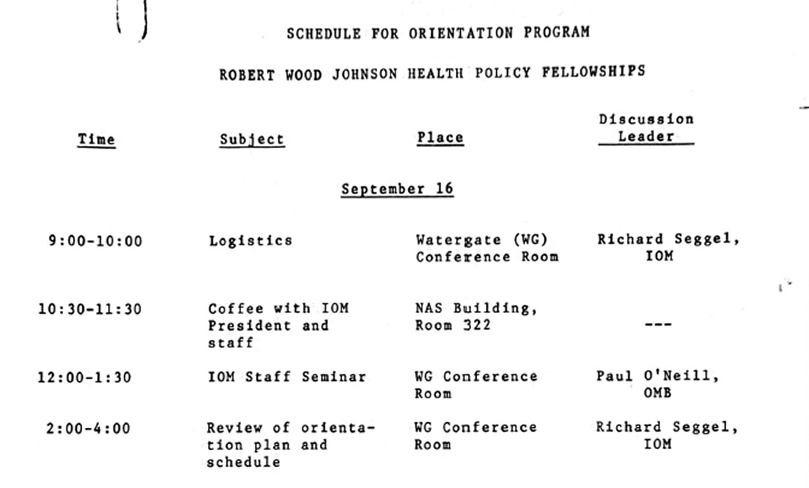

On September 16, 1974, the first six fellows gathered for their first day of the program’s three month orientation. Little did they know how much they would learn over the next three months and that they were embarking on a program that would become the envy of health policy practitioners across the nation.

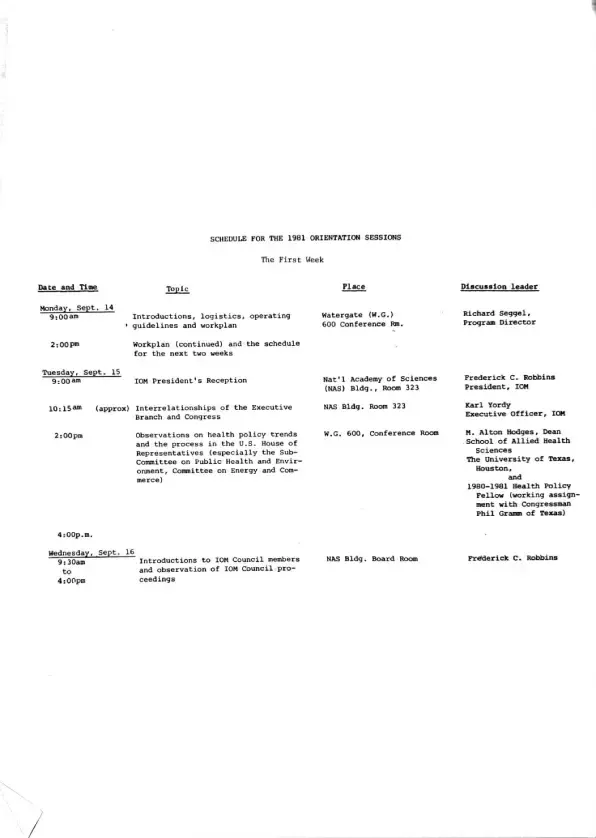

Explore a sampling of historical orientation schedules

1976

Stories from our fellows

The Reading List

Every summer before the fellowship officially begins in September, the incoming fellows get a reading list and a stack of books and articles either mailed to their homes or sent electronically. The list, like orientation itself, changes every year based on the receommendations of the past cohort.

The 1974 reading list included 27 articles, books, and documents. Today it boasts *******.

Explore the reading lists from the first year and the 50th year:

A Day in the Life

The IOM orientation schedule was hectic, often involving traveling across town. I was surprised to discover that all of the fellows were able to maintain their enthusiasm and interest in the orientation over the entire two months. Furthermore, it provided an opportunity for us to become familiar with Washington’s geography.

— Edward Wimberley, 1989-1990 fellow

About half the meetings were held at the IOM, and half at the offices of the relevant agency. This worked out quite well, as it allowed for efficient use of time (IOM site) and becoming familiar with the city (outside sites). Refreshments and health snacks were provided at the meetings (and lunch when appropriate). This alleviate gastric obstacles to paying attention during the meetings, and made me feel that the IOM staff were very concerned about our welfare.

— Philip Goodman, 1989-1990 fellow

Field Trips

From the start of the fellowship, the orientation program included a field trip to Atlanta, Georgia to visit the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and a Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) (reorganized into the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 1980) regional office.

In 19**, the program added trips to two states, often with contrastiing approaches to health policy, to the orientation schedule. Each cohort has the opportunity to select which states they visit, and they typically meet with the state’s Medicaid officials, academic leaders, and key decision-makers across the health and healthcare landscape. These hands-on experiences help prepare fellows to become health policy leaders at every level.

By the end of orientation, fellows are stuffed to the brim with health policy knowledge and contacts, and they are ready to start contributing. But before they can enter their placement offices and start working, they have to interview. Select the XXXX button to learn about the placement office interview process and 50 years of fellows’ experiences interviewing for Congressional and Executive office positions.